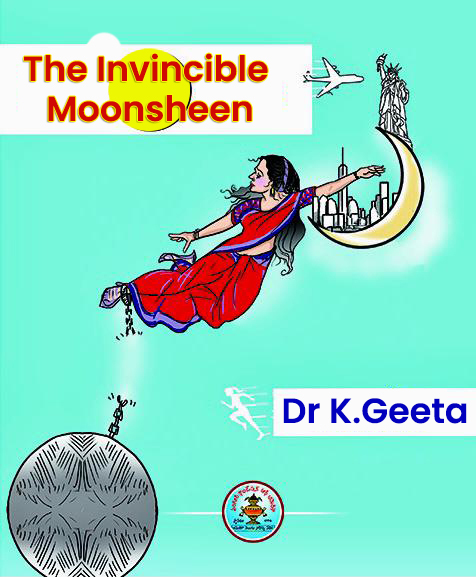

The Invincible Moonsheen

Part – 40

(Telugu Original “Venutiragani Vennela” by Dr K.Geeta)

English Translation: V.Vijaya Kumar

(The previous story briefed)

Sameera comes to meet her mother’s friend, Udayini, who runs a women’s aid organization “Sahaya” in America. Sameera gets a good impression of Udayini. Four months pregnant, Sameera tells her that she wants to get a divorce and the circumstances are conducive to it. Udayini asks her to listen to the story of “Tanmayi” and pursue her to make her own decision after listening to the story. Tanmayi and Shekhar, who met at a wedding ceremony, go to marry with the permission of their elders. After the marriage they started their new life in Visakhapatnam. A boy was born to the couple in a year of their marriage. Tanmay engages in her studies deeply and enjoys the friendship with her colleagues forgetting all about her household disturbances. Her parents came to stay with her for a month while Shekhar is away on his long-term camp.

***

“Girls Government Junior College”

The name on the board blurred before Tanmayi’s eyes as tears welled up. She could not see the letters anymore.

She would soon be a lecturer in this very college. A government job! The thought filled her with joy. Where had her life begun, and where had it led her? She had achieved this not through ease, but through stumbling, falling, and rising again. At every step there had been obstacles, yet she had stood like a soldier — wiping her own tears, tending her own wounds, and walking forward. She had been her own army, her own courage.

She drew in a deep breath. If life had not thrown difficulties at her, would she have been so persistent? Would success have tasted this sweet? Would her heart have rejoiced so much in finding a job far away from her people? A smile flickered at her lips at the absurdity of her thoughts. This college was, in fact, better than the one where she had studied her own intermediate course in her hometown.

The moment she stepped inside, her memories of those days returned like a flood. the lecturers, the laughter, the mischief, the songs and games. Those were the years when her dream of becoming a lecturer had first been born. Now, unexpectedly, that desire had come true. She laughed inwardly at the thought of her own lecturers seeing her in this role. What if she had been posted in the same district? Perhaps she might even have worked alongside one or two of the young lecturers she had once studied under. But such fortune was impossible at this distance.

Her thoughts turned to Siddhartha, who had guided her during the interview. She had meant to tell him of her success, but by then he had already been transferred. Perhaps she would never meet him again. She sighed. So many acquaintances in life ended abruptly, unfinished.

As she passed through the gate of the campus, she heard the children whispering, “New madam…” Their eyes followed her, some giggling, some pushing each other playfully, some peering through the classroom windows. She smiled and waved. In the middle of the campus stood a flagpole, around which stretched long buildings with wide verandas.

In the office, the typist at his typewriter looked up and said, “Namaste, madam.” Two attendant girls, standing beside him, smiled and echoed, “Namaste, madam.”

Tanmayi sat hesitantly in the chair before the table marked Principal. She could feel every eye in the room upon her, curious, weighing the newcomer who had arrived with a suitcase in hand. She smiled faintly and said, “I’m coming from Visakhapatnam.”

“From so far?” they gasped, jaws dropping.

At that moment, Principal Yadagiri entered and greeted her warmly. “Ah, madam, when did you arrive? Will you have some coffee?”

After the formalities of her joining were complete, he said, “Come, I’ll show you the classrooms,” and led the way.

Behind the main row of buildings, another block stood. It was a large college, with four to five hundred students. He showed her the computer lab. “We recently got a grant from the MP fund, but we don’t have any instructors. No one here knows enough,” he said, troubled.

Tanmayi remembered the basic computer course she had once taken at Vivekananda School.

“I’ll try, I know a little,” she offered quickly. And at once, another memory stirred, Prabhu, the only computer expert she had known.

What if I ask him to teach here? she wondered. Then aloud, she said, “A friend of mine is an MCA student. Do you want me to ask him?”

“Good, ask him once,” the principal replied.

From a nearby room, children’s voices rose in song, clear and melodious.

“Shall we go that way first?” she asked eagerly.

He looked confused for a moment, not understanding. Realizing it was the difference in dialect, she added, “The song is so good, I want to hear it once.”

“Oh… that’s all. Let’s go, madam,” he said, smiling.

But as they entered, the singing stopped, replaced by a ripple of laughter.

“This is your new Telugu madam,” the principal announced.

The students smirked. “Sir, she looks like an English teacher!” they teased.

“Are they saying I look like their English teacher? Or that I am their English teacher?” she wondered, puzzled. Though she knew dialects, she had never encountered the raw rural accent before. She realized how much she had yet to learn.

Still smiling, she asked, “I love singing. Who taught you?”

A voice piped up from the back: “Annalu taught us, madam.” The class burst into laughter again.

Pantasenulara miku pada padaa nondanaalu

Senusilaka lara miku semata sukkala vondanaalu

ekkadivi pantaraasulu

ninginundi theesukochhara

pachha pachhani aakilalla

Sukkaloola Katha Rasi

sankalona bidda nunchi

sakkanainaa kankulu ganna

mokkajonna senulaaku

netthinundi poolumudisi

nelaporalo kaayaksasi

endalallo vaadipothe

endipovunu pillansni

poddithoni aatalade

podduthirugudu senulaku

mattilona kalisina gaanii

maranamannadi nikuledu

itthanaalai oruguthuvunnaa

putlakoddi pantalainaa

Yet the song lingered in her ears long after she left. The social consciousness in those young voices, barely out of high school, yet singing with such conviction haunted her. The song, written by Jayaraju, seemed more powerful than many professional compositions she had heard. Her eyes filled again. How small personal struggles seemed before the larger struggles of society! How noble, the gratitude of a farmer to his crops!

That day, she also noticed how many children lacked proper clothes or shoes. Poverty was raw here, unlike in her town.

These children are mine now. I must do something for them, she resolved.

In the staff room, she was greeted warmly. “Welcome, madam.” Most of the lecturers were elderly men; only a couple of new girls taught Botany and Commerce. The English post had been vacant for some time. A part-time lecturer was on maternity leave, and for now the principal himself was teaching English.

During introductions, one of them asked casually, “What does your husband do, madam?”

“I’m a divorcee. I don’t wish to speak of him,” Tanmayi answered, direct and steady.

An awkward silence fell, but it passed quickly. By evening, the staff had embraced her as one of their own, and she felt at home.

When the day ended, Taiba, the attendant, walked beside her. The streets were neat and clean, with no open drains, no garbage strewn about.

“Cleanliness is possible because the sewers flow underground, the streets are paved with flagstones, and the garbage isn’t thrown on the roads,” Taiba explained.

Tanmayi thought of her own town, where drains overflowed, and mosquitoes and flies swarmed.

“Yes, I see…” she murmured.

“And the staff?” she added, changing the subject. “Everyone is very kind.”

Taiba smiled. “It’s all in your mind, madam. If your mind is good, everything appears good.”

Tanmayi looked at her in wonder. What a simple, profound truth she had spoken!

When asked about a room to rent, Taiba said, “Don’t worry, madam. Stay at my house. My husband is in Dubai.”

Her warmth touched Tanmayi. Taiba was her own age, with a bright smile and a shining nose ring. She had worn a burqa when leaving college. Together, they walked fifteen minutes to her house. On the way, Tanmayi stopped at an STD booth to call her mother and tell her of the new village. She also spoke to her son.

I must go home this weekend and bring Babu. I’ll take two days’ leave including Sunday, she resolved.

Then she called Prabhu.

“A post in a college?” Prabhu laughed loudly.

Tanmayi frowned, puzzled. “Why are you laughing?”

“If you call me to visit your college, I’ll surely come. But leaving my corporate job to take a small-town post? Impossible,” he said.

She nodded, patient. “Don’t worry, Prabhu. I remember you were searching for a job when we last met.”

“Oh, I forgot to tell you,” he chuckled. “I got a job, I’m in the computer lab. I’ll come on Saturdays to teach you, all right?”

She sighed deeply as she ended the call.

“Who was it, madam? Your husband?” Taiba asked.

Tanmayi shook her head gently. “No…”

They turned into a street where a small three-room house stood. Its porch was clean, paved with flagstones. Each room had been built for separate rental. One was locked. Behind another was a small kitchen with a stove, and at the back, a tiny bathroom.

She liked it immediately. The rent was cheap compared to Visakhapatnam. With a smile, she paid Taiba fifty rupees more than asked, along with a month’s advance.

“I’m so happy, madam. Eat with us until your things arrive,” Taiba said, delighted.

She brought a folding bed for Tanmayi. As soon as she lay down, sleep pulled at her eyes.

Thoughts flickered like sparks in the darkness. A new place. A new life.

In life, the things we expect do not always happen. And sometimes, the unexpected arrives like a blessing. This job, this town, was one such blessing. Excitement swelled within her, but so too did the ache of distance, from her parents, from the soil where she had grown. Slowly, an anxious heaviness began to creep into her heart.

*****

(Continued next month)

A post graduate in English literature and language and in Economics. A few of my translations were published. I translated the poems of Dr. Andesri , Denchanala, Ayila Saida Chary and Urmila from Telugu to English. I write articles and reviews to magazines and news papers. To the field of poetry I am rather a new face.