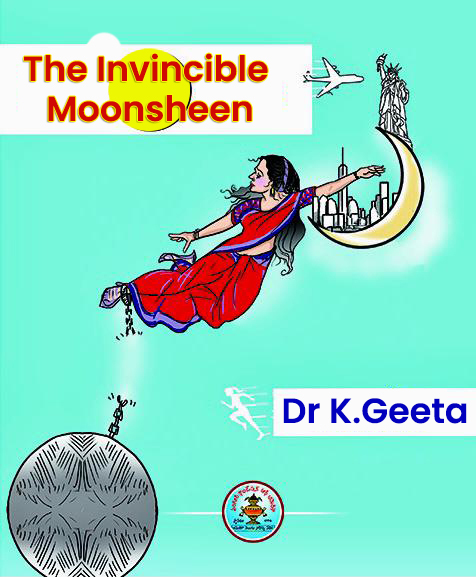

The Invincible Moonsheen

Part – 41

(Telugu Original “Venutiragani Vennela” by Dr K.Geeta)

English Translation: V.Vijaya Kumar

(The previous story briefed)

Sameera comes to meet her mother’s friend, Udayini, who runs a women’s aid organization “Sahaya” in America. Sameera gets a good impression of Udayini. Four months pregnant, Sameera tells her that she wants to get a divorce and the circumstances are conducive to it. Udayini asks her to listen to the story of “Tanmayi” and pursue her to make her own decision after listening to the story. Tanmayi and Shekhar, who met at a wedding ceremony, go to marry with the permission of their elders. After the marriage they started their new life in Visakhapatnam. A boy was born to the couple in a year of their marriage. Tanmay engages in her studies deeply and enjoys the friendship with her colleagues forgetting all about her household disturbances. Her parents came to stay with her for a month while Shekhar is away on his long-term camp.

***

The following week, Tanmayi went back home and brought her son with her. While arranging the kitchen utensils, an unexpected wave of sorrow swept over her. These utensils are mine, this kitchen is mine, this house is mine… she, like any ordinary young woman, had innocently dreamt. She still remembered where each item had been bought. In fact, it was her mother who had sent all the utensils needed for her married life. But since they were not new—already used for many years—Shekhar’s mother had taunted her. Though Tanmayi saw her mother’s love in the sarees and utensils given from home, he and his mother saw them as nothing but a trick to get rid of old things. Every time he frowned at the sight of those gifts, Tanmayi had set them aside and bought a few new things. That’s how a small buttermilk churner and a sieve bought at Poorna Market came into her hands.

That day was still vivid in her memory—the early days of marriage. Since her husband was not from that town, it was she who had to go out and purchase whatever was needed. On the advice of the girl next door, she went to Poorna Market not only to buy the sieve and churner but also vegetables for the week. She took the bus, passed the crowded Jagadamba junction where people were gossiping about the cinema halls around, and instead of that chatter, she lifted her gaze to the sky. Clouds were thick, as if preparing for a drizzle. When she crossed the road and entered the market gates, it was already muddy, as if rain had just poured. In the slush stood rows of shops—from vegetables to utensils—some on gunny sacks on the ground, some on carts, some in small stalls. Pushing, spitting, cursing, people thronged about. Tanmayi held her cloth bag over her shoulder, tucked her little purse inside her blouse, hitched her sari pleats higher, and, with great difficulty, bought what she needed and stepped out. Her eyes lingered lovingly on the new churner and sieve. Only such things gave her peace of mind. She had even asked her mother for the ones at home.

“What? Were your husband’s first criticisms not enough? Why bring old things again? Anyway, you set aside everything I gave you and bought new ones. Those I gave have been lying here all along—I never touched them,” Jyoti replied harshly.

Tanmayi’s legs went weak. Yes, her husband had once spoken hurtfully to her mother—that was true, and it pained her still. But now she was only her mother’s daughter. Why should her mother still drag out the past and speak so cruelly?

Not stopping there, when Tanmayi asked her mother to come with her, Jyoti said, “If I follow you around, who will look after your father here? Do you think this is like your in-laws’ home—servants everywhere? They are landlords; money means nothing to them. But I don’t like the idea of leaving your father here and going with you.”

Not even a token gesture—she didn’t give her daughter any household provisions to carry back. That very day milled rice arrived at their house, yet when Tanmayi asked for a small bag, Jyoti snapped, “Why carry rice so far? Buy it there.”

Tanmayi sighed inwardly. With him, life was full of sorrow; separated from him, it was still sorrow. Such misfortune—may no one else suffer like this. Even knowing that her daughter now lived alone, why did her mother torment her with sharp words, as if untouched by concern?

As soon as she boarded the train, sleep would not come. By dawn, her eyes were burning, but she forced them shut, thinking bitterly, It’s all my cursed fate!

When she got off the train in the morning, she waited long for a bus. Then she learned that only city buses stopped there, and for the red buses she had to go to the main bus stand. Carrying her baggage, she started walking in search of an auto. Her son held her sari edge tightly, trying to keep pace with his mother. The bus stand was extremely crowded. Burdened with luggage, she could not compete with those rushing inside for seats.

Just then, a young man beside her said softly, “Give me that, I’ll help,” and took one of her bags. He even easily secured a seat for her.

“Thank you so much,” Tanmayi said gratefully.

Once inside the bus, sleep overwhelmed her. The boy had already curled up against her. The young man sitting beside the boy asked, “Which town are you going to?”

She told him.

“Oh, that’s my best friend’s hometown. I keep visiting,” he said.

Tanmayi only nodded sleepily.

Unmindful, he asked, “Didn’t your husband come with you?”

“No,” she murmured, closing her eyes.

At some stop the bus halted. The cries of children selling corn cobs—“Makka buttal, makka buttal!”—woke her up.

The young man at the window bought three and quietly handed two to her. Before Tanmayi could react, her son eagerly grabbed one and began to eat. That very morning he had refused biscuits, yet now he devoured the roasted corn as if he had always loved it. Watching him eat with such relish, Tanmayi felt a pang of emotion.

Not wanting to be misunderstood, she said, “Thank you.”

He replied, “My hometown is close by. Do visit sometime,” and scribbled his name and phone number on a scrap of paper, handing it to her.

“Murali…” Seeing the name, memories of Vivekananda school—Venkat, Murali—flashed before her.

Life is so strange! Murali had always helped her whenever she was in trouble. Even now he was helping. She turned and greeted him with folded hands.

At the bus stand, she took a rickshaw. The design was unlike those at home—the seat and footrest were at a much lower level. Her son stared in wonder. Back home, rickshaws had high seats where you could dangle your legs. As a child, when they went to the movies, she used to walk there, and on the way back they took a rickshaw. She would sit between her parents near their legs, and by the time they reached home she would always be fast asleep. She used to hate being woken up to walk into the house. She wished they would let her sleep in the rickshaw all night.

“I must surely do the same when I grow up,” she used to think.

That memory brought a smile to her face. Stroking her son’s hair as he chattered, she gazed into his bright eyes. Midway through his stories, he drifted into sleep. She caressed his head lovingly. However close he was to his grandparents, the sparkle he showed with her was never the same with them. And whenever she left him behind, his anxious eyes haunted her. Bearing in the womb, giving birth—this is what they call the bond of the womb!

“Now we’ll live happily together, my dear!” she whispered, hugging him warmly.

She enrolled him in a good school in town. Bought uniform, books, bag, tiffin box, water bottle—all the necessities. On the way back, her son pointed at ice cream and Five Star chocolates.

“I’ll buy you, but only one,” she said.

After wavering, he finally chose ice cream.

As they walked home, he asked sweetly, “Amma! Can we buy Five Star tomorrow?”

Tanmayi disliked lying to a child. “No, my dear. We buy such things only once a month.”

Seeing his puzzled face, she explained gently, “From Amma’s salary, we spend some, and save some. If sudden troubles come, who will give us money?”

He nodded as if he had understood. At home, she covered his books with brown paper and wrote his name neatly. She cleared a shelf and arranged his school things.

The very next day, he pestered her that he would not go by school bus.

“Why, child?” she asked sternly.

He pointed to children going with their parents on scooters and bicycles. Tanmayi’s heart ached.

No matter how hard she tried, she could not bring him up without reminders of his father. How could she? The more she thought, the heavier her head grew.

Unexpectedly, when the college typist asked if she would join a chit fund, she agreed.

Until then she had not known what a chit was, or why people joined them.

“For middle-class people like us, when money is urgently needed, this is the only way to borrow with low interest,” the typist explained as he collected her first installment.

The very next day she started scanning the newspaper classifieds for second-hand ladies’ two-wheelers.

That evening, as she scrubbed pots blackened by the kerosene stove, her neighbor Taiba asked, “Madam, why don’t you apply for a gas connection?”

“I may apply, but they say it takes a year,” Tanmayi said.

“First buy a gas stove, Madam, until the connection comes, you can use one of my double cylinders,” Taiba offered.

Tanmayi sighed. Spending her little savings on a stove and cylinder was difficult.

She told Taiba so.

“Oh ho, Madam! Do you think people like us have plenty of money when we buy things? Everyone manages on credit!” Taiba laughed.

That evening she dragged Tanmayi to a shop selling stoves and mixers on installments. “Bhaiyya! Show to our Madam a good stove,” she said.

Tanmayi protested, “Wait, first let me figure out how to pay—”

But the shopkeeper said, “Madam, you are from the college, right? First choose what you like. Then pay little by little.” He showed her a few stoves.

She asked, “Show me a good-quality one, but cheaper.”

He brought two more from inside and gave her a slip with the installment plan.

The cheapest stove cost 900 rupees, but on installments it came to 1200—100 rupees a month for twelve months.

Seeing her hesitation, he said, “I’ll give it to you for 1100. Just pay 200 now and take it.”

Taiba laughed, “Bhaiyya, you never give me such offers!”

The shopkeeper replied, “Madam came here from a far away place. We should treat her well!”

Tanmayi pulled 200 rupees from her purse and handed it over.

“The stove is good. Madam, every month buy one item like this. By year’s end, you’ll have everything. Buying all at once is impossible,” Taiba said, carrying the stove for her.

“Buying all at once never worked in my life,” Tanmayi sighed.

“Things don’t last forever, Taiba,” she added with a deep breath.

“I don’t understand such big sayings, Madam. Come, let’s buy some roasted sweet potatoes,” Taiba said, stopping.

As she broke one open and offered, she noticed Tanmayi looking longingly at the corn sellers.

“I love corn cobs,” Tanmayi confessed.

With Taiba’s cheerful chatter beside her, the walk never felt long. Tanmayi thought to herself, If only life were always like this girl’s company!

Her son too walked without complaint, happily listening to their talk.

*****

(Continued next month)

A post graduate in English literature and language and in Economics. A few of my translations were published. I translated the poems of Dr. Andesri , Denchanala, Ayila Saida Chary and Urmila from Telugu to English. I write articles and reviews to magazines and news papers. To the field of poetry I am rather a new face.