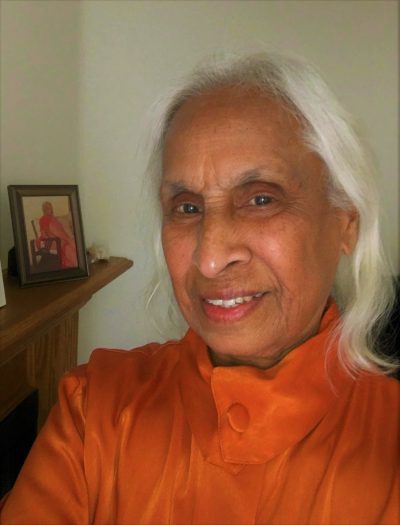

Telugu Women writers-13

-Nidadvolu Malathi

The reviewer also noted that a reader from the audience sent a note to the podium in the form of a poem, “Oh voyagers! Bring our women writers down to the earth,” implying women writers were writing unrealistic stories. Lata said in response, “Why don’t you look up and acknowledge us,” implying possible that the problem was not women writers writing unrealistic fiction but the readers refusing to acknowledge them as writers.

On 17 January 1975, Andhra Jyoti weekly published a special edition on women writers (Responding to the United Nations’ announcement of the year as the International Women’s Year. It was also the Telugu festival Sankranti time.). The magazine included brief bios of several women writers (from which I quoted on previous pages) under the title, Racayitrula Parichaya Malika [introductions to the women writers featured in the current issue]. The editorial included a comment that, “… unfortunately, in our country, women are as much responsible for trailing behind. They themselves should make the effort to free themselves from the shackles of irrational beliefs, dated customs and meaningless traditions.”

In the same issue, some articles by women writers discussed important issues. Vasireddy Kasiratnam wrote an article “Is there a need for separate conferences for women?” The author noted the changes in the mode of writing from descriptions of women’s body parts to current issues but failed to make a strong case for the need for separate conferences for women.

- Satyavati wrote about the criticism of women writers. She quoted several cartoons and jokes about women writers and commented that several male writers were also writing ludicrous stories, and some of them were using female names. “In the past women were portrayed in cartoons as aggressive with rolling pins in their hands and now they are being portrayed with pens in their hands,” she commented, and ended the article with a note inviting the cartoonists to portray male writers also in their cartoons. The article described what was happening in the field of criticism of women writers but did not go any further. There was no clear analysis in regard to how or whether such cartoons impacted women’s writing.

In short, it would appear that by the mid-seventies women writers were becoming increasingly conscious of the social issues, unfair reviews of their writings by male establishment, and their own responsibility or eagerness to set the record straight. That is a step forward from the previous century and a step in the right direction.

Women Writers as a Target of Ridicule

Before going into the details about sarcasm and ridicule, a brief note on culture is relevant here. I have commented on this aspect earlier regarding Molla and Muddupalani. Additionally, I would like to relate some of the comments made at the Visakha Sahithi meeting on October 12, 2002. One of the examples, given by Malayavasini, a senior professor and writer, is a poem written to ridicule women’s writing. She said,

A woman, named Koonalamma, wrote poems, with her name as a caption at the end of each verse. Imitating her style, a male writer wrote the following poem:

kundale bhaandamulu

kukkale sunakaalu

aaduvaare streelu O Koonalammaa!

In this poem, a set of words from colloquial Telugu, ‘kundalu’ [clay pots], ‘kukkalu’ [dogs], and ‘aaduvaaru’ [women] are equated with a set of Sanskrit terms, ‘bhaandammulu,’ ‘sunakaalu’ and ‘streelu’, implying a false sense of elevation in status. Malayavasini commented that replacing the colloquial terms with pedagogic terminology (damsel for woman, for example) might appear complimentary on the surface but in reality meant to ridicule the female author, Koonalamma.

A second example Malayavasini quoted was from a weekly magazine. She referred to a set of photographs of women writers published in Andhra Jyoti in November 1982, under the caption, “Racayitrula Bommala Koluvu,” [a display of dolls] and commented that the caption was hardly complimentary to the writers’ creativity.

She also added that, probably, we would have more women writers, if this kind of ridicule and humiliation had not been prevalent in our society. themselves to this caption in the magazine either. However, several writers have used and continued to use the exchange of wisecracks, teasing and picking on each other as part of creating humorous episodes. It has been commonplace in our families for centuries. They are especially acceptable norms among family members like brothers-in-law, sisters-in-law, and husband and wife.

Placed in juxtaposition, these observations—Subrahmanya Sarma’s protest against Sahitya Akademi’s decision and his subsequent comment and, Malayavasini’s objection to the use of the caption, bommala koluvu (published in the same Andhra Jyoti, of which Subrahmanya Sarma was editor)—highlight the complex nature of personal relationships in our society in bold relief.

By the late seventies, the practice of ridiculing women writers found their way into the popular magazines. The magazine pages were filled with cartoons and jokes on women writers.

I shall discuss the humor and culture in detail later. For the present, it would suffice to say that the women writers did not take the jokes and ridicule seriously. They went on writing and publishing.

There are also instances where women writers themselves made satirical comments. Bomma Hemadevi, a prolific writer in this period, made a tongue-in-cheek remark. She said, “Sometimes my husband gives me little money out of the goodness of his heart and tells me to go shopping, buy something for myself. And with that money, I buy paper to write stories.”

It is quite normal for a woman writer to enjoy a private joke or even share it with a friend. But publishing it in a popular magazine certainly implies that she felt free enough to do so; it was intended to be a joke on the people who were complaining about lack of economic freedom for women.

Honestly, I believe it requires a separate study, a job for cultural anthropologists, to identify how far this practice of ridicule influenced the creativity of women. In Andhra Pradesh, support and ridicule existed side by side.

*****

(Contd..)