Telugu Women writers-7

-Nidadvolu Malathi

Marital Status

Regarding marriage, most of these writers have shown some kind of independent thinking. Each of them seemed to have taken a stand in their own way.

Achanta Sarada Devi mentioned that she had ample opportunity to read books because of her marriage with Janakiram in 1944. Malati Chendur married her maternal uncle at the age of 16. Responding to a question by Sivasankari, whether her husband had supported her in her literary career, Malati Chendur responded rather jokingly, “If Chendur had not married me his life would have progressed along different lines. He would have had seven or eight children and would be roaming around on a cycle with vegetable baskets.” [Original in English]. In June 2001, I requested her to elaborate on that comment, asking if her comment meant that she was the smarter one between the two of them. Her husband N. R. Chendur responded on her behalf and said, “Malati was being frivolous.” Further, he referred to another incident, in which she was quoted as saying, “People refer to me as Saraswati [Goddess of Learning], and I’d say he [husband] is the Brahma [the creator and husband of Saraswati] who made me Saraswati”

- Ramalakshmi was also facetious about her relationship with her husband, Arudra, acclaimed writer, critic and literary historian. Ramalakshmi said their first encounter was when Ramalakshmi had asked him to write a preface for her first anthology, Vidadeese Railuballu [The trains that separate people]. She said that he had written the preface, but never read her writings after that.

These stories speak of the complementary and congenial nature of marital relationship in our culture. It is common for couples to be casual, cheery and exchange witty remarks without being offensive.

Vasireddy Sitadevi said she resisted her parents’ attempts to arrange her marriage and went to Madras to pursue her studies.

Ranganayakamma had an arranged marriage at the age of 20, separated at 26, and divorced at 32. She later married her friend and a professor, nine years younger than herself (“Make a note of it; it is important,” she said to me at the interview). Her husband introduced her to Marxist literature, which encouraged her to study further and write books on the subject.

Evidently, Telugu women attached very little importance to the fact whether their marriage was arranged or otherwise. If the marriage was arranged, they worked through and developed a healthy relationship. In the cases where the relationship went sour, they took the matters into their own hands and resolved their issues in ways that suited them best.

Familial Status

Literary heritage was a contributory factor in their self-expression. In a recent interview, Turaga Janaki Rani stated that her mother and aunt were writers, and she was related to Gudipati Venkata Chalam (1894-1979), a highly controversial writer. Chaganti Tulasi is daughter of Chaganti Somayajulu (1915-1994), a reputable progressive writer. Usha Rani Bhatia is daughter of Kommuri Padmavatidevi who had published extensively during the period, 1930-60.

Kalyanasundari Jagannath stated that she wrote her first story at the insistence of a family friend and writer, Mallampalli Somasekhara Sarma. She wrote a story and showed it to him. He read it and took it to the office of Bharati himself; and it was published right away. Kalyanasundari also quoted Somasekhara Sarma as saying, “I knew you could write but did not expect you to be this good.” A second comment she had received was from the most famous poet of our times, Sri Sri. Sri Sri even promised to translate her story into English, never did though. He advised her, “In future, try to write tragedies without killing your heroes”.

Ranganayakamma said that her father had encouraged her in her teen years to write for a caste-oriented journal he had been running. She mentioned that her caste, padmanayaka caste, was known for cockfight sport. She hated the sport and developed a hatred for the caste system eventually. In her later writings, it took a much stronger tone. She added that her father used to subscribe to popular magazines, which helped her to develop an interest in reading books.

The experiences of Turaga Janakirani and D. Kameswari summarize women writers’ experiences concerning the response from family members. Turaga Janakirani, responding to my question whether her family members encouraged her to write, said:

“If you are asking me whether somebody came to me with a pen and paper and told me to sit down and write, the answer is no. I wrote whatever and whenever I felt like writing. The publishers and magazine editors encouraged me. I was even proud of my writing since whatever I sent was published right away. Sometimes, the editors would write to me their comments on my stories. Gora Sastry, editor of Telugu swatantra, was one of the editors.

In addition, I am not afraid to speak my mind. For instance, I know Chalam [her mother’s uncle] possessed excellent philosophy but it was not well balanced; his vision was lopsided at best, and I told him so. I’ve written my views on his philosophy in my book, Maa Taatayya Chalam [My Grandfather Chalam]. He liked me a lot. That does not mean I have to agree with everything he had said.”

This kind of free interaction of writers with family members has been part of our culture until the end of the third quarter of the twentieth century.

- Kameswari said she started writing after her marriage. She was a voracious reader; used to read anything and everything she could lay hands on. She said:

I have read Chalam and Kovvali novels also, sneaking behind my parents back [Chalam and Kovvali novels were viewed as objectionable for their adult content by most of the parents]. I am just a housewife, had no higher education. I started writing only after I had my three children. Nobody said anything one way or the other. Occasionally, my husband would read and say something if he felt like. I never felt I was being mocked for writing stories.

Money had never been a motivation. I admit it feels good to see a few rupees as my own. It is not much but it’s gratifying but that has never been a motivation for me to write.

- Vasundhara Devi, responding to my question whether she and her husband, R. S. Sudarsanam, critic and scholar, discussed her writings, wrote to me (the original in English):

I had read almost all of my husband’s literary works before publication. He did not tell me to read or not to read his manuscripts.

He would read my stories only after they had been published. He never made any comment. I remember however, he telling a newspaper interviewer that I would never accept his suggestions or make changes.

But we discussed religious and spiritual matters; that is one area where we traveled together.

At my home, I never thought my family had noticed my writing. For me, it was just a part of daily activities. Now, looking back, I can recall a couple of incidents that could be construed as encouragement. On one occasion, my father took me to the Andhraprabha Weekly office [a two-hour trip by bus]. My sister subscribed to Readers Digest in my name during my teen years. My mother would suggest reading stories of Hindu saints. I am not sure whether it was supposed to be my religious training or the beginning of my writing career, but the stories certainly captured my interest. My uncle and writer, Nidadavolu Lingamurti, once commented on a children’s story I had written for a children’s magazine. That is about it. Like most of the women of my time, I was reading whatever I could lay my hands on. Nobody in my family objected to my reading Lata or Chalam [both unacceptable by the standards of some families at the time]. Nobody in my family ever said anything that could dampen my spirits. In recent years, my second brother, Sitarama Rao has been giving me support for my literary activities like attending meetings and meeting with writers.

From what I have known and seen in interviews with the writers, it appears that women in the middle-class families did not meet with opposition; they did not have to conceal their writings for fear of ridicule. In one instance, the husband kept answering my questions while the writer kept quiet. Later I came to know that there was a tragedy in the family, and he was helping her to cope with the loss. In another instance, husband served us coffee and snacks while we were talking. Sometimes, men were present in the room but only as audience. In some families, brothers did some writing but that did not hinder women from writing. Sulochana Rani said she used to fair copy her brother’s fiction, which encouraged her to try writing herself. She said that when her first story was published, the family members thought it was her brothers’ story, and he published it in her name. The brother had to convince the family that she wrote the story and not he.

My impression from my interviews and personal experience has been one of positive note. In saying so, I am aware that I am stepping on a slippery slope. In recent years, a few of the sixties and seventies writers have been expressing opinions contrary to my perception. I shall address this topic later.

The negative attitude towards women writers and ridicule started in the late seventies after women writers had reached the height of their success.

*****

(Contd..)

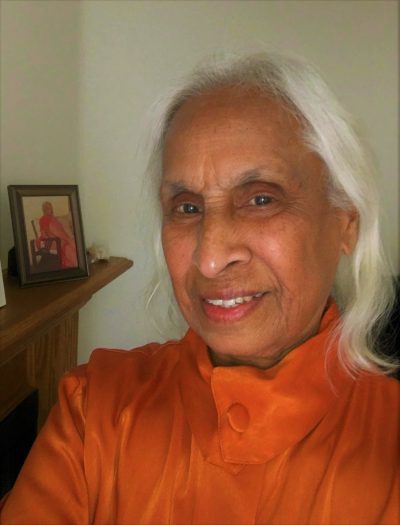

Nidadavolu Malathi born in 1937 to progressive parents, Nidadavolu Jagannatha Rao garu and Seshamma garu. She has Masters’ degrees in English Language and Literature, and in Library and Information Sciences. She has been writing fiction in Telugu since early 1950’s.

She moved to America in 1973. In 2001, she created a website, www.thulika.net, with a goal to introduce Telugu culture and customs through translations of stories and original essays on various topics. She has translated over 100 stories and wrote several critical essays. The website has been a good source for researchers in several universities abroad. In 2009, she started her blog, Telugu Thulika (www.tethulika.wordpress.com) where she has been publishing her Telugu stories, essays and poetry.

Her translations have been published in 2 anthogies, From my Front Porch (Sahitya Academy), and Penscape (Lekhini, Hyderabad). Her short stories in Telugu are published in 2 anthologies, Nijaanikee Feminijaanikee Madhya (BSR Publications) and Kathala Attayya garu (Visalandhra). She also has published eBooks: Eminent Telugu Scholars and other Essays (Non-fiction), All I Want Was to Read, My Litttle Friend (Short Stories.)