Telugu Women writers-8

-Nidadvolu Malathi

Economic Status

Economic status did not play a crucial role in women’s writing in the early fifties. In the past, supporting the family was not woman’s responsibility. Therefore, economics was not a part of the equation. The situation has changed, drastically after women entered the workforce. Ironically, the question became not one of economic freedom but of economic status. In general, even when women had the money, they were not in a position to spend it as they pleased. The new economic status women had achieved hardly worked to their advantage. The educated woman was caught up in a double bind. The writers I spoke with stated unequivocally that income was not a motivation for them or their families. This situation had been a major theme in the fiction of the fifties and sixties stressing the writers’ awareness of the irony.

One of the major contentions of the western critics has been that women writers did not succeed in the field of literature due to lack of economic freedom. Famous Indian writers, like Kamala Das and Anita Desai profess this argument. In Andhra Pradesh, however, to the best of my knowledge, economics did not play a role in the women’s writing during the period under discussion. Koganti Vijayalakshmi, a contemporary writer, stated that Telugu women never wrote in the past or present to make money but only to satisfy their internal craving to express themselves; and secondly, to fulfill their obligation toward society, which again is a modern concept.

In the past, the financial aspect was not a concern for women. With the advent of modernization in the post-independent India, the power of currency has come to dominate, giving rise to a different set of values.

In the late fifties, publishers and magazine editors started offering remuneration for fiction. Not all but most of the popular magazines like Andhra Patrika and Andhraprabha Weekly were offering nominal amounts for stories published in their magazines. Some magazines of good standing, like Telugu Swatantra and Bharati, offered no financial reward to my knowledge. (In a recent interview, a famous male writer told me that he had insisted on being paid and had been paid by Telugu Swatantra).

In those days, getting a story published in Bharati was an honor in itself. Several women writers like Dwivedula Visalakshi and Kalyanasundari Jagannath found their way into literary circles through their publications in Bharati.

A few writers mentioned about the economic constraints at home during their childhood. Malati Chendur said that she was only six months old when her father died and her mother had to assume the family responsibilities on her own. Ranganayakamma referred to the financial constraints at home in her younger days. Significantly, in both the cases, the family’s financial problems did not curb their creativity. In fact, no woman writer had mentioned that her family discouraged her from writing for any reason, economic or otherwise.

Ranganayakamma mentioned about her financial hardships after separation from her first husband. She said she moved to Hyderabad for her eye surgery, and stayed with friends, who were also her supporters and fervent readers of her writings. Referring to their kindness, she quoted a popular Telugu proverb, which roughly translates as, “I can’t settle their debt even if I had given my skin to make sandals for them.” Interestingly, while attacking ferociously the male domination and female oppression in her writings, she also gathered a large circle of male friends.

The point I am trying to make is Telugu women writers had received support from their families, publishers, magazines, and readers, while expressing their views, antagonistic at times, in their fiction during this particular period.

IN SOCIETY

For women writers of this era, the situation outside was similar to the environment at home. Up until the achievement of independence, the country was focused on the fight for freedom, in which women participated actively. After achieving independence in 1947, the next logical step was to rebuild the nation in step with other developing countries, which meant educating the mass, men and women. As a result, an overall reevaluation and renovation of traditional values took place.

The three major movements, namely, the Social Reform Movement, the Independence Movement and the Library Movement contributed immensely to popularize women’s writing and explore women’s creativity. Just in one decade, from 1920 to 1930, the number of Telugu magazines had nearly doubled, from 136 to 240. Several of them were caste-oriented reflecting the strong community bond within the castes.

Weekly and Monthly Magazines

While most of the women writers in the previous generation continued to publish in the magazines exclusively for women like Hindusundari and Gruhalakshmi, a new generation of writers started writing fiction and publishing them in the magazines that were not marked ‘for women only’. Popular magazines like Andhra Patrika, Andhraprabha Weekly, Bharati, and Telugu Swatantra welcomed fiction by women writers with great enthusiasm. Although they were not marked exclusively for women, the magazines were instrumental in promoting women’s writing, especially fiction. Most of these editors and publishers were freedom fighters and champions of the women’s movement in the past, and as such, entertained liberal views.

Andhra Patrika, started in 1908 by Kasinathuni Nageswara Rao, was the first weekly magazine, which promoted progressive views. The publisher’s mission statement was, “We hope to provide knowledge relating to our society and the world for all our people.” Significantly, unlike in the past, the magazine did not identify women as a separate class requiring education. Nevertheless, Andhra Patrika featured several women writers. The magazine was a great success enjoying a membership subscriptions of 2000, which was considered big at the time.

A second magazine, Bharati monthly, also started by the same publisher, Nageswara Rao, became a milestone for its high literary standards. Although most of the writers/scholars were male, Bharati also featured women writers like Turaga Janakirani, Dwivedula Visalakshi, K. Ramalakshmi, Illindala Saraswatidevi, Kalyanasundari Jagannath, Malati Chendur, and other prominent women writers of the time.

The third magazine among these trendsetters was Andhraprabha weekly, launched in 1938. Narla Venkateswara Rao, known for his sophistication, and several innovations in journalism, became its chief editor and ran it from 1942 to 1959. Under his leadership, the magazine’s circulation went up from 500 in 1942 to 72,000 in 1959. The weekly magazine gave importance not only to political issues but also to social, economic, industrial, and educational issues, and thus, laid foundation for new trends in journalism. One of them relevant for our discussion was the feature column Pramadavanam with Malati Chendur as the columnist. The column was an instant success and made Malati Chendur a household name. Referring to her accomplishment, Malati stated, “I have dealt with all topics under the sun in a series of articles and in a ‘question and answer’ format for over 45 years.” The topics ranged from beauty tips to health, family counseling and cooking. She also included short articles on foreign women writers. In her interview with me in 1982, Malati mentioned that she had been taking some of the ideas from foreign magazines like Ladies Home Journal. This feature could be one of the many reasons for the circulation of Andhraprabha Weekly to reach the astronomical figures mentioned earlier.

In the early fifties, Telugu Swatantra also encouraged women writers. Gora Sastry and Khasa Subba Rao were editors of Telugu swatantra at the time. K. Ramalakshmi, Ranganayakamma, Turaga Janakirani, P. Saraladevi, and Nidadavolu Malathi were some of the writers who were introduced through this biweekly magazine.

Another magazine that made enormous service to women writers was Andhra Jyoti Weekly, which was started in July 1960 with Narla Venkateswara Rao as its chief editor. Puranam Subrahmanya Sarma joined the magazine in 1967, He was one of the high-ranking editors that appeared to have supported women writers. I will elaborate on this a little later.

*****

(Contd..)

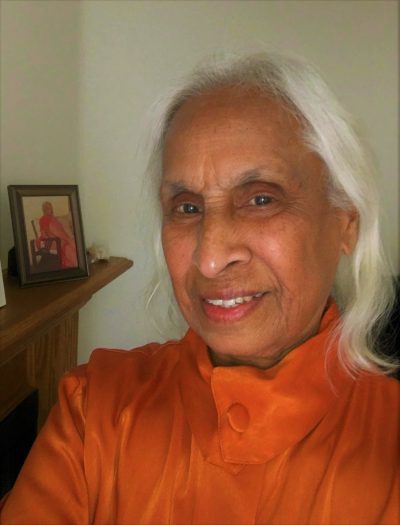

Nidadavolu Malathi born in 1937 to progressive parents, Nidadavolu Jagannatha Rao garu and Seshamma garu. She has Masters’ degrees in English Language and Literature, and in Library and Information Sciences. She has been writing fiction in Telugu since early 1950’s.

She moved to America in 1973. In 2001, she created a website, www.thulika.net, with a goal to introduce Telugu culture and customs through translations of stories and original essays on various topics. She has translated over 100 stories and wrote several critical essays. The website has been a good source for researchers in several universities abroad. In 2009, she started her blog, Telugu Thulika (www.tethulika.wordpress.com) where she has been publishing her Telugu stories, essays and poetry.

Her translations have been published in 2 anthogies, From my Front Porch (Sahitya Academy), and Penscape (Lekhini, Hyderabad). Her short stories in Telugu are published in 2 anthologies, Nijaanikee Feminijaanikee Madhya (BSR Publications) and Kathala Attayya garu (Visalandhra). She also has published eBooks: Eminent Telugu Scholars and other Essays (Non-fiction), All I Want Was to Read, My Litttle Friend (Short Stories.)