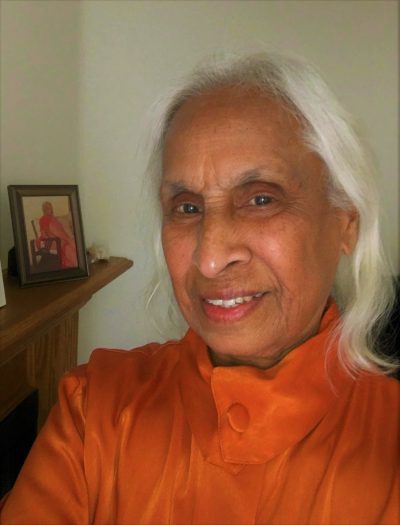

Telugu Women writers-17

-Nidadvolu Malathi

Synopsis:

Kannamma was a working class woman. After her husband had left her and her baby for another woman, she was looking for work to make a living. She took several odd jobs, but each time, she found herself cornered. Every man she had come across assaulted her or made sexual advances towards her. Exhausted and desperate, she arrived at the doorstep of Radha, a middle-class woman. Radha listened to her sad story and took her in.

Radha had enormous faith in her husband’s ethical conduct. She strongly believed that he was as good as the Lord Rama, known for his ekapatnivratam [Avowed monogamist].

Radha received a telegram informing that her grandma was seriously ill. Radha went to visit her and found out that grandma was not ready to die after all. She spent a few days with her brothers and sisters joyously and returned home.

At home, Kannamma told her that Radha’s husband had made sexual advances towards her while Radha was away. Kannamma told her to keep an eye on her husband and left for good.

Radha confronted Satyanarayana. He first accused Kannamma of lying, then made excuses for himself and eventually apologized. He even offered to search for Kannamma and bring her back.

Radha was disillusioned. She realized that there was no such thing as honesty in a man. A desperate cry came ripping through her heart.

The story makes use of the hardships of a lower class woman to drive home a point—the lack of security for women in middle-class families.

Issues surrounding unwed mothers were also depicted in the fifties stories. Turaga Janakirani told me one of the stories she had written in 2002. The story, “Jaganmatha” [Divine Mother] is as follows:

A woman gave birth to a boy out of wedlock. The father walked away. Two of her friends decided to visit her. One of them was self-righteous, hung up on her high moral code. She was intent on chiding the mother for committing a huge, stupid blunder. The second, a kindly disposed friend, wanted to shower pity on the new mother and show her support.

They both went to visit the new mother. Much to their amazement, the mother was very happy with her newborn baby. She had no use for either the pity of one friend or the scorn of the other. The two friends found themselves at a loss for words and left.

On their way home, they realized that they both had been wrong in their assumptions about the mother’s situation. Apparently, the mother did not consider herself to be in a “situation”.

Janakirani said that the story was received very well. She also told me about an incident that followed. Malladi Subbamma was a famous feminist and social reformer. Janakirani said that her husband read the story, turned to Subbamma and said, “Look, you organize meetings, deliver speeches, and write hundreds of articles on feminism. Janakirani has conceptualized the entire feminism in these four pages.”

The next story depicts a man who was living with two women under the same roof. In the early fifties, the story “Vallu Padina Bhupaala Ragam” [The Wake up Song They Sang], written by P. Sridevi, became a classic not only for its theme, the man-woman relationship, but also for exposing the shallowness in the middle class lifestyles and the values they had been supposedly upholding.

A young man, Rama Rao, (Ramam) was barely sixteen when he finished high school. His father sent him to the city to find a job. His father, several of his uncles, aunts and other relatives, had warned him to stay away from his cousin Srinivasulu. They all told him that Srinivasulu was living an immoral life, namely, living with two women.

In the next few days, however, Ramam learned a few more things about Srinivasulu as well as his relatives in the city. Srinivasulu gave Ramam his side of the story.

Srinivasulu had lost both his parents while he was a teen. His father had left him a huge chunk of land. His uncle, mother’s brother, took him under his wing, and married off his daughter Suseela to Srinivasulu. Moreover, he took Srinivasulu’s property, mismanaged it, and drove him (Srinivasulu) to near bankruptcy.

Devastated, Srinivasulu sold the rest of the land and moved to the city to start a new life along with his wife. A few years passed by. They had four children.

Varalakshmi, a rich, young widow happened to meet Srinivasulu at the hospital. She proposed to move in with him and he accepted it. He told himself, “Why not? Am I not man? Why refuse a rich and beautiful woman when she is willing to walk into my life, on her own accord, knowing full well I was married?”

Srinivasulu brought Varalakshmi home. Suseela saw the benefits of it and accepted the arrangement. Srinivasulu added, “True, Suseela does complain, especially when others are around. At the same time, she has no problem enjoying Varalakshmi’s wealth. And all those uncles and aunts, who continue to disparage me and my lifestyle, have no scruples; they don’t hesitate to borrow money and other things from me, knowing fully that they’re taking money from the very woman they’d been disparaging.”

He handed over the financial management to Varalakshmi, with vengeance and enjoyed it, too.

For Rama Rao, the complexity of this entire gamut of relatives was an education in itself. He quit searching for jobs, much to the chagrin of his father, and decided to go to college. He was convinced that he needed more time to study life.

The narrator was clearly describing a given set of values defined by the three individuals, for themselves and in defiance of the accepted social norms. Whether this is a story of man-woman relationship or a business proposition depends on the reader’s perspective.

Women writers of this period did not limit themselves to women’s issues exclusively. There was a considerable amount of fiction written on topics central to family and society. The topics included women in social context, middle-class values, human suffering and emotions.

*****

(Contd..)