Telugu Women writers-15

-Nidadvolu Malathi

3. THEMES

In the preceding chapter, we have noted how Telugu women writers moved away from bhakti tradition of self-effacing to the awareness of self (identity) following the nationalist and social movements. It is important to note that the original intent of the social reformers and educationists was not instilling a sense of self-awareness in women. The education for woman was intended only to make her a better housewife.

However, most of the writers of the fifties were children or young adults at the time of the Nationalist Movement and thus grew up with values of freedom and commitment.

Secondly, the Women’s Education Movement encouraged women to read. Majority of the women writers of this decade had formal education up to high school at least.

At the end of the forties, the last vestiges of national spirit, the reform movement, and the library movement continued to influence the writers and readers. Consequently, the women readership also augmented which in turn gave further support for women writers.

In the early fifties, the women writers started looking for themes other than bhakti and romanticism. Their themes reflected traces of the past as well as the new awareness of self, which was still in the formative stage. Because women still stayed at home while improving their reading and writing skills, and because the magazines and family members encouraged them to write, they started to write fiction. They were writing about what they were familiar with—the home and the family.

With the collapse of zamindari system and the princely states, the upper class women also became middle-class. A new set of middle-class mores emerged subsequently. The writers depicted their life—changing values, social norms, especially the newly emerged class of the educated women and the issues emanating from new status as an educated woman, the ensuing economic problems, and most importantly, the changing relationships within the family.

A few writers depicted characters from the ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots’ often with a romantic slant. Depicting the poor however was rare except as secondary characters, and when they did, it was from the perspective of the upper classes. The poor were often illustrated as symbolic of a perception that was relevant to the middle-class. We hardly find stories of the poor from their own perspective in women’s writing in this period.

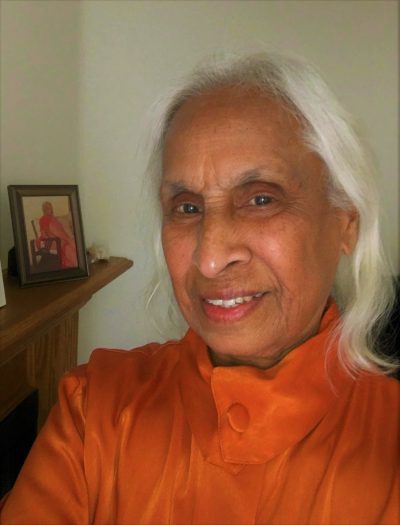

During the two and a half decades in question, about twenty to thirty women writers contributed profusely and regularly to the weekly and monthly magazines. Some sixty to seventy writers wrote occasionally. Most of them produced voluminous literature in the form of novels and anthologies. Tenneti Hemalata [Lata], Ranganayakamma, Malati Chendur, Dwivedula Visalakshi, Vasireddy Sitadevi, D. Kameswari, and Madireddy Sulochana, were some of the many writers who had successfully portrayed the multifaceted terrain of contemporary life. Writers like Kalyanasundari Jagannath, Chaganti Tulasi, Turaga Janakirani, R. Vasundhara Devi, P. Saraladevi, Acanta Saradadevi and Nidadavolu Malathi wrote fewer in quantity but distinctive in quality. All these writers had a firm grip on the middle-class problems at home and tangible issues in society—the problems young women were facing because of their higher education, and the fast-changing moral and ethical values. A few writers like Bhanumati Ramakrishna and Yeddanapudi Sulochana Rani wrote fiction in a lighter vein nonetheless captivating. Both of them found a niche of their own.

One factor that worked both for and against the women writers of this period was the volume of fiction they had produced. On one hand, it helped to escalate the circulation figures for the magazines, and the writers to attain a celebrity status. On the other, the amount of literature they were producing set off the elitists to undermine the value of women’s writing. A common comment among the scholars at the time was that the women writers were producing enormous amount of worthless fiction (this opinion is maintained by some critics even today), the actual word was “trash”. In reality, both men and women produced stories and novels in astronomical numbers in order to meet the demands of the magazines. The women writers succeeded in writing momentous fiction.

Coming back to the themes in this period, Telugu women became aware of their identities for the first time and started portraying the same in their stories. Additionally, they started dealing with a wide variety of social issues.

A few synopses given below reveal the breadth of women’s writing during this period and facilitate further discussion on their talent in the next chapter.

Portrayal of woman’s awareness of her identity varied from a simple knowledge that she was a person in her own right to protesting and then to taking charge of her life.

*****

(Contd..)